Linda Wagner-Martin wrote and published Sylvia Plath: A Biography in 1987, and for many years it was the best Plath biography, enriched by details Aurelia Plath provided. Wagner-Martin first contacted Aurelia in 1984, sending her a draft subtitled A Literary Biography, and then interviewed her. Wagner-Martin secretly tape-recorded an interview and admitted to doing it. Aurelia was hurt and angry. Wagner-Martin's husband immediately returned the tape with apologies.

Aurelia forgave Wagner-Martin and kept in touch until 1990. Wagner-Martin also contacted other people acquainted with Sylvia Plath. In the Wagner-Martin files at the Lilly Library I found information and observations new to me, most of them not in any published biography:

Aurelia, age 13, in 1919 took on the care of her siblings, including her infant brother (born September 1919), while their mother was still weak from influenza and double pneumonia. This experience made Aurelia long to become a mother. (March 9, 1986)

Sylvia's classmate Donald Junkins, quoted as saying that Sylvia in Robert Lowell's poetry workshop looked "mousy," after reading the biography described Sylvia as "all silkwormy and opera-lonely and mono-blonde in that thin straggly way she had with her brain competing with everything in sight." Her lively classmate Anne Sexton outshone her. (Jan. 10, 1988.)

Eddie Cohen wrote Wagner-Martin (Sept. 3, 1985; Oct. 14, 1985) that Sylvia kept all letters she

received, meticulously, as her mother did, and kept copies of her

own letters. Cohen wrote to Aurelia after Letters Home was published in 1975, and from her first learned the details of Sylvia's ruined marriage and how Sylvia destroyed her second novel.

Regarding Plath biographies, "It is strange that nowhere have I read about my own education," Aurelia wrote Wagner-Martin on September 1, 1984. But that was Aurelia's own fault: "In those

days a girl who made high grades kept the fact to herself -- it was

unpopular to be a 'green stocking'! So the secret has been kept all

these years that I [w]as Salutatorian of my high school class and

Valedictorian of my college class. . . I am a retired Associate

Professor Emerita -- really!" Wagner-Martin quoted this letter in this biography and a later one.

Gordon Lameyer, Sylvia's boyfriend in 1953 and '54, wrote Wagner-Martin in 1987 complaining that everyone he met, including Anne Sexton, asked him about Sylvia's virginity. Lameyer's unpublished memoir said Sylvia had sex with him only after secretly losing her virginity to a stranger because, Lameyer said, Sylvia was afraid to seem to her boyfriend like a beginner or unskilled.

|

| Senior housing. Aurelia probably added the "Peace" sticker. |

|

Dido Merwin criticized Wagner-Martin and

Letters Home for not mentioning astrology when astrology had been essential to the Hughes-Merwin friendship. What Dido wrote in this 1985 letter about Ted and Sylvia's visit to Lacan is retold in grating detail in Dido's postscript to Anne Stevenson's 1989 Plath biography

Bitter Fame.

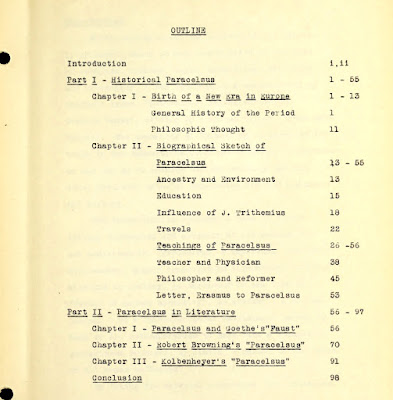

The senior-housing complex where Aurelia lived her final ten years, North Hill, had 454 residents, most of them strangers to Aurelia. The Wagner-Martin archive includes a Christmas greeting picturing the complex (Dec. 9, 1985; pictured) and a postcard photo of North Hill (June 25, 1990).

Elizabeth Sigmund alleged in a phone interview that Ted deliberately moved Sylvia to their Devon country home, "the most alien place he could have put her," to keep her isolated.

"I have read, weeks ago, your [manuscript]. . . I am very pleased with most of it. . ." Aurelia wrote to Wagner-Martin in June 1984. Aurelia objected chiefly to the the portrayal of herself. She told Wagner-Martin she had not been an absent parent but was always home when school-aged Sylvia and Warren came home from their extracurricular activities.

Perry Norton's ex-wife Shirley (Mrs. Tom Waring) wrote on March 28, 1985 that Mrs. Mildred Norton, mother to young Sylvia's friends Perry and Dick, was a "charming but manipulative mother" whose sons had to excel academically, win scholarships, and become doctors. "And from Mildred too was the frantic message against physical attraction" that made sensitive Perry a worrier. Mildred sent eldest son Dick away to boarding school because he was becoming attracted to a girl.

It was known in the 1980s that a character named "Esther Greenwood" appears in a 1916 short story, "The Unnatural Mother," by first-wave feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman. ("Greenwood" was Sylvia's grandmother's maiden name, and Sylvia had a cousin Esther in Boston.)

Aurelia congratulated Wagner-Martin on her "most attractive book" on October 29, 1987, but not without bitterly criticizing again the portrayal of herself, which caused her a "pressure-heart attack." On January 10, 1989, Aurelia wrote a thank-you note for two copies. And thanked the author again on June 25, 1990, for sending the "fine English paperback."

|

A sample of Ted's and Olwyn's objections to Wagner-Martin's manuscript.

|

Young Sylvia and Warren were always invited to "professors' kids" summer picnics and Christmas parties, according to a July 13, 1984 interview with C. Loring Brace (1930-2019). Aurelia at these events met Loring's mother Margaret, a Boston University graduate who "may have had a class from Otto Plath. She befriends Aurelia and always felt sorry for her, married to Otto. He was a real tyrant, and Aurelia suffered. So her need for companionship of other educated women was real. Mildred Norton and Margaret Brace were sorority sisters at B.U. . . Made the Plath-Norton connection much easier." Wagner-Martin paraphrased this information, leaving out the reference to Otto.

The thickest folder in the Wagner-Martin Box 1 holds letters from Olwyn Hughes, starting in 1982. In 1986 Olwyn read Wagner-Martin's final draft and sent the biographer 15 pages of deletions and changes [a sample is pictured] required by Ted and herself. Olwyn kept requesting changes until Wagner-Martin balked. Olwyn then denied Wagner-Martin permission to quote from Sylvia's poems. Despite the Plath Estate's efforts, Wagner-Martin's biography was published and she went on to publish another, more specifically literary biography, Sylvia Plath: A Literary Life (1999; second edition, 2003) and four other Plath-related books I know of.