It's bilingual, but its first half is mostly in English, and reading Aurelia's thesis online I liked best its sympathetic portrait of Swiss physician and surgeon Paracelsus, "the Luther of medicine," bold enough to replace the ancient texts of Galen with medical science -- in the 1500s -- and denounced by enemies and posterity as "the demon doctor." In fact Paracelsus shocked the physicians of his day by saying they should be like Jesus, living humbly and healing the poor for free.

Aurelia Schober first studied Goethe's Faust in German, as an undergraduate, and in her thesis framed the life of Paracelsus as one of the sources feeding into Goethe's multi-faceted poetic drama, written around 1800, and into two related literary works, one in German and one in English (Robert Browning's Paracelsus). "The Paracelsus of History and Literature," 101 pages, capped Aurelia's master's degree in English and German, earned in less than one year, granted in 1930. Here's an excerpt:

Paracelsus told [students] that neither degrees nor books made physicians, only much toil in acquiring the knowledge of things themselves, in studying actual sicknesses, their causes, symptoms, remedies. He, their teacher, was willing to share all his experience, would take his advanced students with him when he visited the sick so that they might watch his diagnosis, learn from his treatment. He would lead them into Nature's apothecary shops -- the fields and forests, and there teach them herbal science.

"I wish you to learn," he would urge, "so that if your neighbor requires your help you will know how to give it, not to stop up your nose, like the scribe, the priest, and Levite, from whom there was not help to be got, but to be like the good Samaritan, who was the man experienced in nature, with whom lay knowledge and help. There is no one from whom greater love is sought than from the doctor."

How true that last sentence was for Sylvia Plath.

| ||||||||||

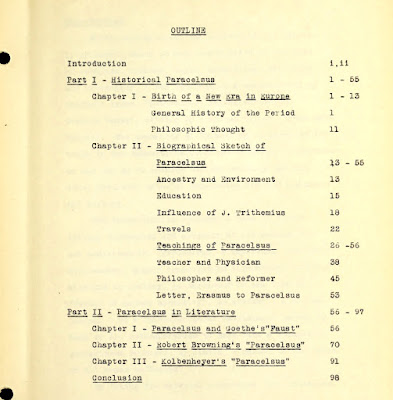

| Aurelia Schober's table of contents. Sylvia Plath read Faust in a dual German-English translation. |