|

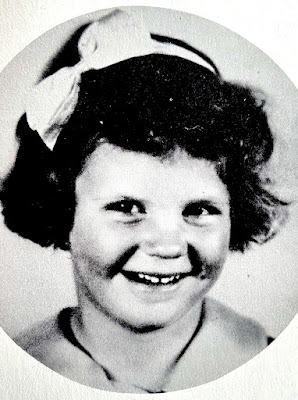

| Sylvia Plath, 1937. |

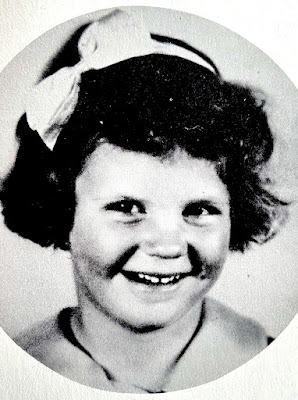

The cut-out photo below is from Aurelia Schober's college yearbook 1928, and I wonder if it's really her; as that yearbook's editor-in-chief, Aurelia surely pasted her own photo, unlabeled, into a yearbook page titled "When We Were Very Young," showing about 30 childhood photos of women in her graduating class.

Sheesh, I thought; that white bow on the kid, big as her head! Leftover Victorian fashion! Dissuading little girls from playing, swimming, running, napping: enforcing feminine passivity.

|

| The reproachful face makes me think this is Aurelia, around 1912. |

Yet most little American girls wore ribbons and bows in the 1910s, '20s, and '30s, when grown American women wore them only to keep their hair out of their faces and and food. In the 2020s exhausted parents tug pink elastic bands onto the sensitive skulls of newborns just to show they are female. Such symbols of femininity and innocence can look cute, and some girls did like wearing ribbons and hairbands, or at least didn't hate them. They maybe thought every female wore them. Here's Sylvia, age three, and her mother at Winthrop in 1936:

I thought Sylvia's mother or grandmother forced her to wear ribbons and bows. But Sylvia spent her life wearing ribbons (pink for her wedding; pale blue for the childhood ponytail her mother cut off and archived), plus bandanas and bands that tamed and trained her hair. That famous "dip" over Sylvia's left eye -- worn long before she went blond in 1954 -- needed a hairpin to anchor it. Where's Sylvia's facial scar in the photo below? It's hidden beneath some quite obvious retouching:

Plath's accessories were pivotal. Her hairpins and watch were removed before electroshock. As you know, Ted Hughes tore off Sylvia's hairband and earrings when they first met. Sylvia mourned "my lovely red hairband scarf which has weathered the sun and much love, and whose like I will never again find." [1] I'd love a Sylvia Plath fanfiction about her hairband and earrings and how she got them back or lost them forever.

It's in the nature of ribbons and hairbands to get lost and replaced. But because Sylvia so often wore hairbands we will always know that this bookstore finger puppet/fridge magnet, even if its tag goes missing, is Sylvia Plath.

In Sylvia's poem "Parliament Hill Fields," an ordinary dimestore barrette makes the first appearance of its kind in literature:

One child drops a barrette of pink plastic; / None of them seem to notice. [2]

In the context of the poem, Plath made that moment resound.

While there are some articles and book passages about Sylvia's apparel, I hadn't noticed that about half the photos of her show her hair controlled with bandanas and headbands. I didn't even see that Sylvia so often wore headwear until I saw the monstrous white bow on what I think is Aurelia Schober. [3] That child's forlorn expression and wavy, light-ish hair have me thinking it's her. About Aurelia's childhood we as yet have no photos and know almost nothing.

By 1962 Sylvia's hair grew long enough to be braided and coiled into its own headband; the style is called a "crown braid" or "coronet." Sylvia exulted over hers and is wearing it in the famous "daffodil" color photos taken in April '62. Poet Amanda Gorman in 2021 started a media fuss by wearing a red headband crownlike, as if women aren't supposed to do that. It's regal.

[1]

Journals, 26 February 1956.

[2] "Parliament Hill Fields," written February 1961.

[3] For really small photos of little Sylvia's really monstrous bows, see the Plath family photos of Sylvia on the endpapers of Letters Home.